Actress slash Director slash Writer slash General Annoyance Lena Dunham makes a silly face at the camera and kisses her mohawked boyfriend before adjusting her ill-fitting dress and slouchily stepping up to the podium to accept her “Best Actress – TV Series, Comedy or Musical” Golden Globe, Robyn’s “Dancing On My Own” playing in the background.

After a speech worthy of Prince Albert, Duke of York—pre-Lionel Logue— Dunham waddles off stage and that’s that. Meet the voice of our generation. At least, that’s how Dunham’s loosely self-referential heroine Hannah describes herself when she tells her parents, “I may be the voice of my generation … or at least a voice, of a generation.” This— Dunham’s accurate portrayal of every twenty-something’s arrogance teetering on crippling self-doubt—is what catapulted her to notoriety among fans of the show.

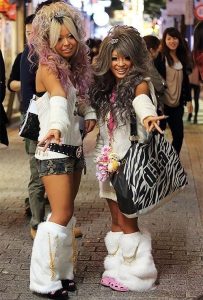

But, a few seconds into her speech and a season into her show, the brains behind HBO’s hit show “Girls” is revealed to be unremarkable at best, dangerously uninnovative and artificially narrow in perspective at worst. Ironically, “Dancing On My Own” is an all-too-fitting song for Dunham, who has come repeatedly under fire for her show’s unrealistic portrayal of gentrified Brooklyn and it’s reliance on stereotypical gay archetypes. Dunham’s Brooklyn is not the Brooklyn we know.

Let’s back up: during a wildly successful first season last year, the fanfare for “Girls” ran concurrently with critiques claiming that Dunham’s vision of Brooklyn fell short of the realities. There were absolutely no minorities, for one, in Dunham’s world.

Dunham brushed the accusations off as unfounded, before half-assedly adding that she doesn’t see race the way her critics do. It was the first test of Dunham’s abilities to confront criticism and she failed miserably, claiming that as a “half- Jew, half-WASP,” she was simply unable to depict the life of a modern-day African- American woman or man. She stopped just short of commenting on whether or not she had any black friends.

The plot thickened when in an almost unmistakable nod to her critics (although it was said to have been filmed very shortly after season one), season two kicked off with Hannah straddling Donald Glover topless. The move fell flat with critics, however, who were unimpressed by the showy and deliberate stunt. Four episodes into the second season and Glover is the lone black character of relevance on the show. It seems Dunham’s critics will have more time to criticize the show. In the meantime, we’ll move on.

Critics of the show have also noticed that Hannah, at least until recently, was paying absolutely no bills. (The end of season one alluded to the fact that her best friend Marnie was helping her make ends meet.) If “Sex and the City”—which “Girls” is often hailed as the 21st Century’s answer to—was criticized for being so flashy that it did not make any financial sense (1990’s Carrie Bradshaw would have been absolutely swimming in credit card debt), certainly “Girls” lies at the other end of the spectrum. Hannah is unfathomably poor, too, but at least she’s doing it in believable thrift shop sandals. Carrie tried to pull it off in Manolo Blahniks.

And while we’re here; it is true “Sexy and the City” did a terrible job of portraying ‘90’s New York’s economy, but it did a lot better of a job portraying gay men at the time. “Sex”’s Stanford Blatch was indeed an anomaly in television at the time—he was a successful gay man who wasn’t motivated entirely by sex. Sure, he had relationships and they of course included sex, but Stanford was a far cry from the token over sexualized, promiscuous, and effeminate gay stereotype of the time.

Dunham’s Elijah is a return to poor form. If Stanford Blatch and “Will and Grace”’s Will Truman were two steps forward, Elijah a step back. Introduced in the first season, he takes a bit more of the spotlight in the second season by…having sex with Hannah’s best friend Marnie. The encounter spurns an exploration of bisexuality, which is of course welcome discourse, but is discourse that stands on the shoulders of disgusting stereotypes.

The criticisms of Dunham’s Brooklyn, of course, are almost pointless. She is the artist and she is free to manifest her vision in the way she best sees fit. She truly does not owe anybody—including the black and gay communities—anything. But as consumers, as the people to whom Dunham is catering to, as the living and breathing parts of the New York and Brooklyn Dunham is cashing off of, we also have a right to demand more accurate representations of ourselves, and to demand higher standards from the media we consume.

She has the option of ignoring those calls—truly, no hard feelings—or taking them into account as valuable feedback and working to construct a show that is not simply a white middle class woman’s reality.