“I’ll forgo sending along my lengthy CV, but in a nutshell, I have taught reading and writing to students from 8 to 80, in public schools, independent schools, and out-of-school time programs. I founded and direct an organization that runs writing retreats and workshops for educators. I am a Pushcart Prize-winning writer, the author of thirty novels for young people, and numerous short stories, essays and articles for adult readers. I have two masters degrees and am working on a doctorate. And… I earn $6,050 for a four-credit course at Pace. The university affords me no health benefits, though I am teaching in person during a pandemic, in a small, poorly ventilated room.”

This is an email sent by English Professor Eve Becker to University President Marvin Krislov upon her arrival at the school three years ago. The full version is currently published on her blog under the title “See Me, Hear Me, Pay Me.” Professor Eve Becker is of the 85 percent of adjunct faculty making up the English Department as well as of the 822 adjuncts at the University hoping to see pay raises with the renegotiation of the current collective bargaining agreement set to expire in June. Under this current contract, on average Pace adjuncts are compensated 36.3% less than comparable universities- both public and private -across the NYC area.

A collective bargaining agreement is a written legal contract consisting of employment terms agreed upon between employers and a group of employees, or in this case, a union. The upcoming negotiations for this year’s collective bargaining agreement, which is renegotiated every three years, will mainly focus on issues involving job security and more competitive salaries.

Like tenured professors, adjunct professors are university faculty members who instruct classes, create lesson plans, grade papers, and hold office hours—unlike tenured professors, adjuncts are paid per credit and lack the benefits allocated to tenured staff such as job security, health care, sabbatical, sick leave, pensions or retirement funds.

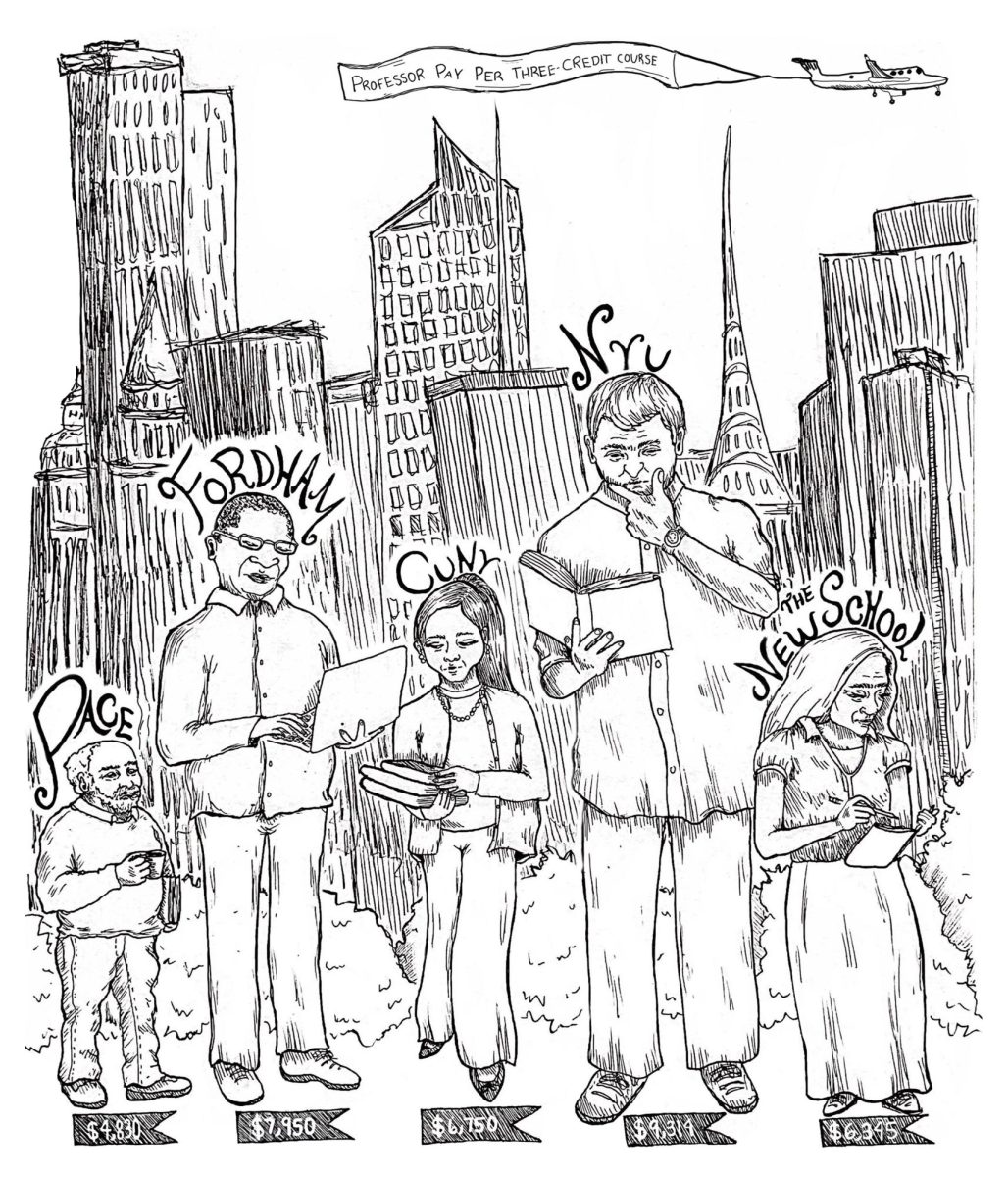

The University is primarily staffed by adjunct faculty, consisting of 63 percent (822) adjuncts and 37 percent (479) full-time professors. This is 11.6 percent above the already substantial national average. The Union of Adjunct Faculty at Pace (UAFP) notes Pace University and Fordham University to be most comparable on the grounds of both having two campuses, a similar percentage of adjunct professors to full-time professors, comparable undergraduate student body populations, akin tuition rates and both adjunct faculties utilizing collective bargaining agreements. Despite these similarities, Fordham professors are being compensated at over 100 percent the rate of Pace adjunct faculty.

Pace adjuncts are compensated between $3,630 to $4,830 per three-credit course depending on one’s title. At most universities, instructors can teach a maximum of 12 credits per semester—although most are only able to secure between three to nine credits a semester at one institution—meaning that adjuncts at the University are making between $29,040 and $38,640 annually before taxes if teaching the maximum amount of 12 credits for both the fall and spring semesters. Annual income for minimum wage in New York State is $31,200.

At Fordham, compensation is based on how long adjuncts have been with the school. Adjuncts within their first three years at Fordham make $7,950 per course and professors who have been there for seven or more years make $8,950 per course; this means someone teaching 12 credits per fall and spring semester has an annual income between $63,600 and $71,600 before taxes which is roughly double what University adjuncts receive.

“My hourly pay rate is running about what it would have been if I’d taken that job at Trader Joe’s, which I applied to at the same time as Pace. TJ’s would have given me medical benefits, which I need for another year, until I turn 65. I would have accrued vacation pay. And been able to get a raise. Employees at TJ’s are largely happy. They get a discount on the delicious vegetarian chorizo and other products. It’s closer to home than Pace. And I wouldn’t wake up in the middle of the night worrying, because the guy in aisle six can’t read or write.”

–Professor Eve Becker, Third Year Adjunct, Continuation from the earlier email

Workload

“While I personally teach in addition to working full-time as a practitioner in my field of study (I would not be able to afford to live in NYC otherwise!) many Adjunct Professors I know teach several courses at multiple institutions in an attempt to piece together the equivalent of a full-time salary you might make as a full-time faculty member.”

-Fifth Year Adjunct

Many adjunct faculty work multiple jobs or teach at multiple universities to make ends meet. Before becoming an adjunct, Becker worked as a teacher at K-12 schools and, despite considering herself partially retired, she does work for several other schools and organizations on top of working as an adjunct professor.

When asked about workload, Becker noted that for every hour spent teaching in the classroom, she spends at least three hours doing work outside of the classroom. At the University, three-credit classes meet in person for roughly three hours a week on average, making the workload for one class about 12 hours a week. Tenth-year adjunct and UAFP Secretary Dr. Beth Roberts noted at one point teaching 18 credits across two universities, which upon using Becker’s stats, adds up to about a 72-hour work week. This does not include the time spent traveling between the two schools, one being the University in the Lower East Side and the other in Westchester.

“When you look at the comparison, it’s just embarrassing that Pace is paying us so little in comparison to how much we do in light of what other schools are getting paid, we as adjuncts, tend to teach, I think over half of the first year.”

-Dr. Beth Roberts, UAFP Secretary, Tenth Year Adjunct

Retention

Pace has a higher-than-average faculty turnover primarily because of the lack of competitive pay offered by the University. According to the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources, faculty turnover averages are about 8.3 percent. For the 2022-2023 school year, the University needed to hire 221 new professors resulting in a turnover rate of 23.8 percent—which is nearly triple the national average. UAFP President and Psychology professor Bill Quinlan is in his 43 years of teaching at the University, starting in 1981, and notes retention amongst students as well as professors to be linked.

“63% of the faculty at Pace is adjunct, teaching 70% of first- and second-year students. The big issue is the uncertainty of whether an adjunct will be hired back because it’s all based upon enrollment. Suppose you connect with a professor and benefit from that relationship, you want to continue pursuing it but the next year they’re gone. Turnover is a serious problem here. We need to attract good professors through good competitive salaries but more importantly keep them. There needs to be continuity. Which is critical for first and second year students. And we want to retain students. That’s critical. Because if you don’t have students to teach, you don’t have a job.”

-Bill Quinlan, UAFP President, 43rd Year Adjunct

New adjunct hires are supposed to be observed for the first three years of their employment to ensure they’re delivering quality education, however, due to the sheer mass of new faculty taken on every year, proper review is unlikely.

It’s not just a Pace problem

College and university mission statements display increasing emphasis on citizenship, community, leadership and world-building through education. Yet, economic competition against other schools in academia has led universities to shift their view of attendees as customers before students.

Second-year Peace and Justice Studies adjunct Dr. Garrett FitzGerald explains, “In the context of higher education, neoliberalism frames education strictly through individual economic choice rather than questions of broader public good—schools become service providers competing for student customers and educational activity is organized around competition within and between schools to minimize cost while boosting returns. Most colleges and universities (including Pace) are technically non-profits, but many have internalized these profit-maximizing neoliberal priorities that create a feedback loop of perceived scarcity and precarity in higher education, as educators in particular are asked to do more with (and for) less.”

To attract more applicants, universities funnel funding into luxury architecture—making sure students have the most up-to-date student centers, dorms, entertainment systems, pools, and gyms.

“Pace University spent 250 million dollars revising dorms, the east wing, and 15 Beekman. I understand the need to be able to attract students, however, you have to attract adjunct faculty to teach at the university. Hypothetically speaking, you can recruit one thousand students, but what happens when you’re left with only one hundred of them.”

-Bill Quinlan, UAFP President, 43rd Year Adjunct

The intention to “sell” a school to incoming students is now a nationwide standard and deeply embedded in college culture. Taking current tuition rates for higher education into consideration, it is not unwarranted for students to have high expectations for the quality of living universities intend to deliver. According to the Education Data Initiative, college tuition and fees for private universities have increased 124.2 percent in the past 20 years (public universities increased 179.2 percent), outpacing the rate of inflation by 171.5 percent.

When asked about her expectations for the university in relation to how much they’re charging in tuition, Political Science and Peace and Justice Studies senior Aryaa Moudgal shared the following:

“I mean if students are paying upwards of hundreds of thousands of dollars in tuition I would expect the campus to reflect that financial commitment. I had to take a class in the east wing of One Pace Plaza before they started doing renovations, and I can tell you that wasn’t an accurate reflection. Obviously if tuition was less I would have different expectations, but with the amount they’re charging—with the amount many universities are charging—I’m anticipating more.”

“Yet at the same time, some of it seems a tad ridiculous. I was living in 33 Beekman when they replaced the study lounge with the Esports Center and I was pretty annoyed because I used to do schoolwork there. Especially when they were already building 15 Beekman—it just didn’t make sense. I’m sure the kids in the Esports center enjoy being gawked at through the first-floor window as much as the students living in 33 Beekman liked losing that space. It seems like the main reason they put it there was just to make it easier to point out when bringing tours through, not taking into consideration how it impacts actual students. While I am genuinely happy the Esports team was given a new facility, it came at the cost of a vital study space.”

This Years Negotiations

Historically, collective bargaining agreement negotiations were noted by UAFP Presiden Quinlan as “drawn out, five-hour sessions.” The first UAFP collective bargaining agreement was carried out in March 2009. For that first agreement, the UAFP and the University met for a total of 54 sessions before coming to a set of agreed-upon terms. Another year saw 20 sessions, and the next 21 sessions with the addition of a federal mediator. Negotiations in 2021 only lasted for six sessions.

Roberts and Quinlan both shared feeling cautiously optimistic about negotiation efforts for this year, citing the presence of Dr. Joseph Franco, Provost for Academic Affairs, as a leading reason. “He listens, he understands. Our first proposal will be April 5th. In the past, I was never even mildly optimistic.”

Sean Coughlin, Assistant Vice President for Public Affairs, shared the following statement in response to a request for an interview regarding the impending expiration of the current collective bargaining agreement:

“Adjunct faculty are an important part of the Pace community, and we deeply value them and their work. Provost Franco recently met with adjunct union leadership to convey our appreciation and indicate that we stand ready to begin formal discussions to negotiate a new contract, effective July 1, 2024. We are confident that everyone will come to a fair and equitable agreement.”

-Sean Coughlin, Assistant Vice President for Public Affairs

Despite the UAFP’s optimism, negotiations this year seem to hold a different weight than those of the past. Adjunct professors have expressed a loss of patience and an inability to continue working under current conditions. Quinlan shared the following statement regarding this year’s negotiations.

“If the adjunct faculty do not agree on a new contract that Pace University has offered, as in they vote no on the new agreement, there will not be a fall semester at Pace University. They can’t open the doors without 63% of the faculty. In other words, we will go on strike. I am cautiously optimistic that this new bargaining group understands the plight of the adjuncts and will do everything they can to prevent it. They do not want a strike.”

-Bill Quinlan, UAFP President, 43rd Year Adjunct

With the fall 2024 semester approaching in just a few months, University adjuncts and students alike eagerly await the results of the new collective bargaining agreement in June.

Anaïs • Apr 28, 2024 at 8:16 pm

That is crazy!

Debbie • Apr 19, 2024 at 4:47 pm

Excellent arguments. We are living in poverty. And we should strike if we don’t begin to get paid competitively.