In the music industry, the role of record labels is crucial, providing resources to the artist. However, it is still the artist’s job to continuously prove to these labels that they are worth the investment. Record labels and Artist and Repertoire Representatives, or A&R, aid in your growth, but their resources can only go so far. Recently, the relationship has shifted; the industry has seemingly taken up new behaviors previously, such as manufacturing picture-perfect boys for young girls to fawn over. But in our new age, boys are no longer marketable. What do young girls want? Why, girls, of course!

The Last Dinner Party seemingly emerged out of nowhere. Despite only having released a single, they were suddenly opening for Hozier, recording for the BBC and securing a nationwide tour. The discourse surrounding the band has been palatable. They perfectly fit into the ‘hippie’ indie girl niche, “whimsigoth” in a way that was seemingly completely cordoned off by Florence + The Machine until now. They deliberately align themselves with this market and seem to capture the trendiest aspects of this aesthetic perfectly. With their corsets, bows, opulent imagery and nonsensical lyrics, they’ve tapped into a piece of the industry that would have been impossible to achieve without several millions of dollars behind them. What caused outrage online, however, was that they had one single out while securing regularly high-profile performance spots like Jimmy Kimmel and “BBC Radio 1.”

Herein lies the key issue: What an industry plant is has been constantly misconstrued. I posit that an industry plant is not an artist managed by a label or with deep industry connections. “Industry plant” describes behavior that labels have undertaken that was previously only reserved for boy bands. It begins with a virtually unknown set of artists launched directly into the public eye with a perfect, fully realized image intending to hit a certain target audience. Whereas artists like Billie Eilish and Ice Spice had a climb aided by virality that allowed them to later secure increasingly more prestige spots, an industry plant’s virality comes from their placement in prestige media spaces, not vice versa.

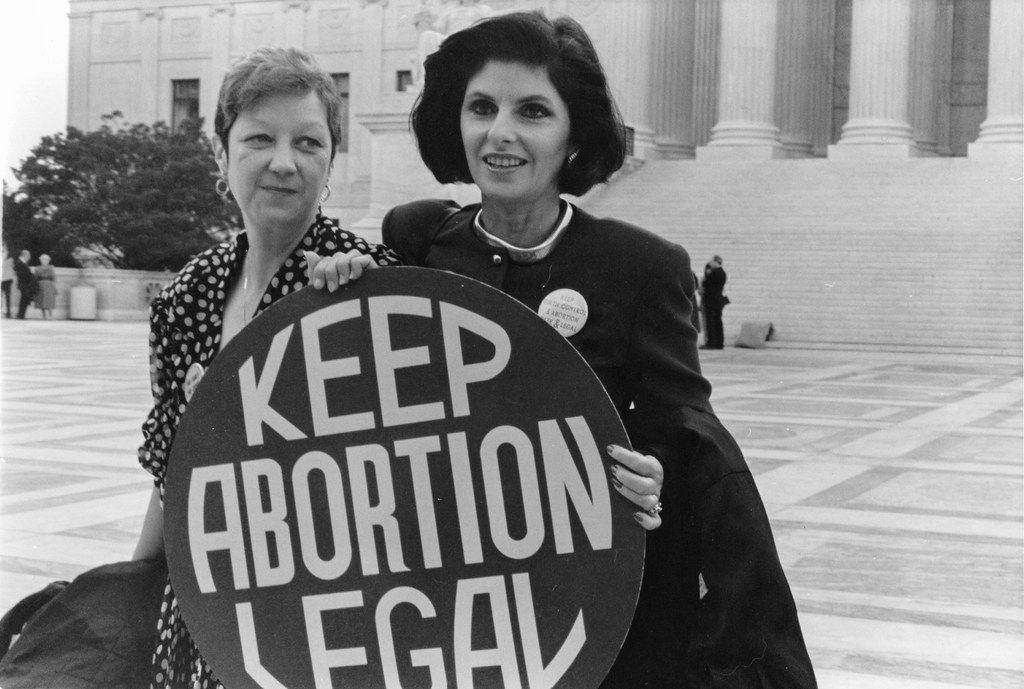

There’s a debate around whether or not it is sexist and, in many cases, misogynistic since many of the industry plant accusations are levied around women. To that, I say this: In music and media, women are substantially more marketable, and although there is something to be said about discounting a woman’s talent by attributing it to something else, this is not the case. Over the years, there have been many accusations towards men. However, women are more likely to be accused of being industry plants because the industry has more incentive to invest in women. The question remains: why should consumers care about the status of industry plants?

When artists are proven to be successfully created for a specific aesthetic, corporations need to invest in artists when they can essentially create their own. This blocks off new artists and diversity and gives power back to the corporations. Aside from the high criticism of the authenticity of art, when the industry controls narratives, it means that diversity is impacted and often restricted to what the market believes is acceptable, especially when the aesthetics that are used to prop up these artists are derived from alternative spaces or cultures cultivated by people of color. The images used to market to the youth usually emulate a particular aesthetic without being tied to its meaning and origin. So, while the artist with industry plant accusations against them most likely isn’t, the behavior these labels engage with is very much tangible and potentially harmful for art.