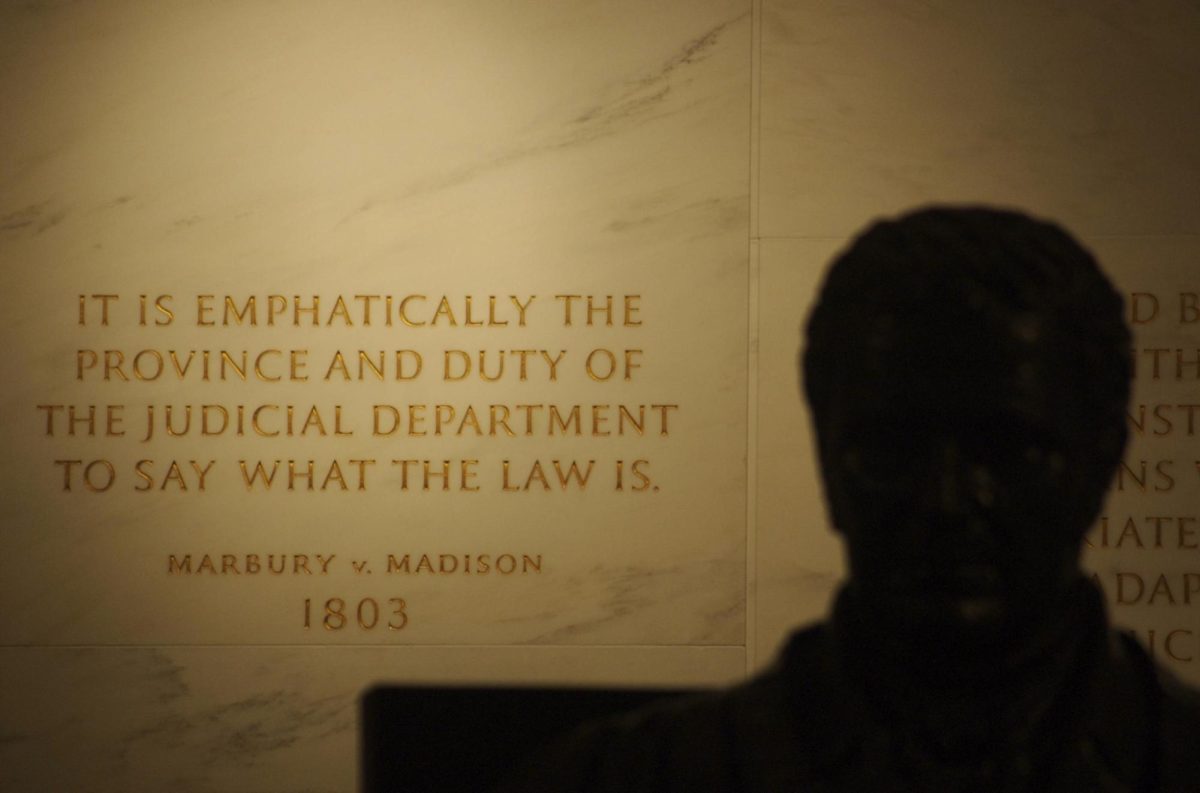

We often go about our daily lives not thinking much about how the Supreme Court shapes the world around us. From the rights we exercise to the laws that govern us, the Court’s rulings impact nearly every aspect of American society. Whether it’s determining what the government can or can’t do or deciding the limits of our freedoms, its decisions echo through history and flow into our everyday experiences. If there were ever a Supreme Court case to wear the “landmark” crown, Marbury v. Madison would be it. This 1803 decision didn’t just shake up the judiciary–it practically built it. Without it, the Supreme Court might have remained the least threatening branch of government, overshadowed by Congress’ purse strings and the executive branch’s military might. Instead, thanks to Chief Justice John Marshall, the Court went from “just some guys in robes” to the ultimate constitutional referee.

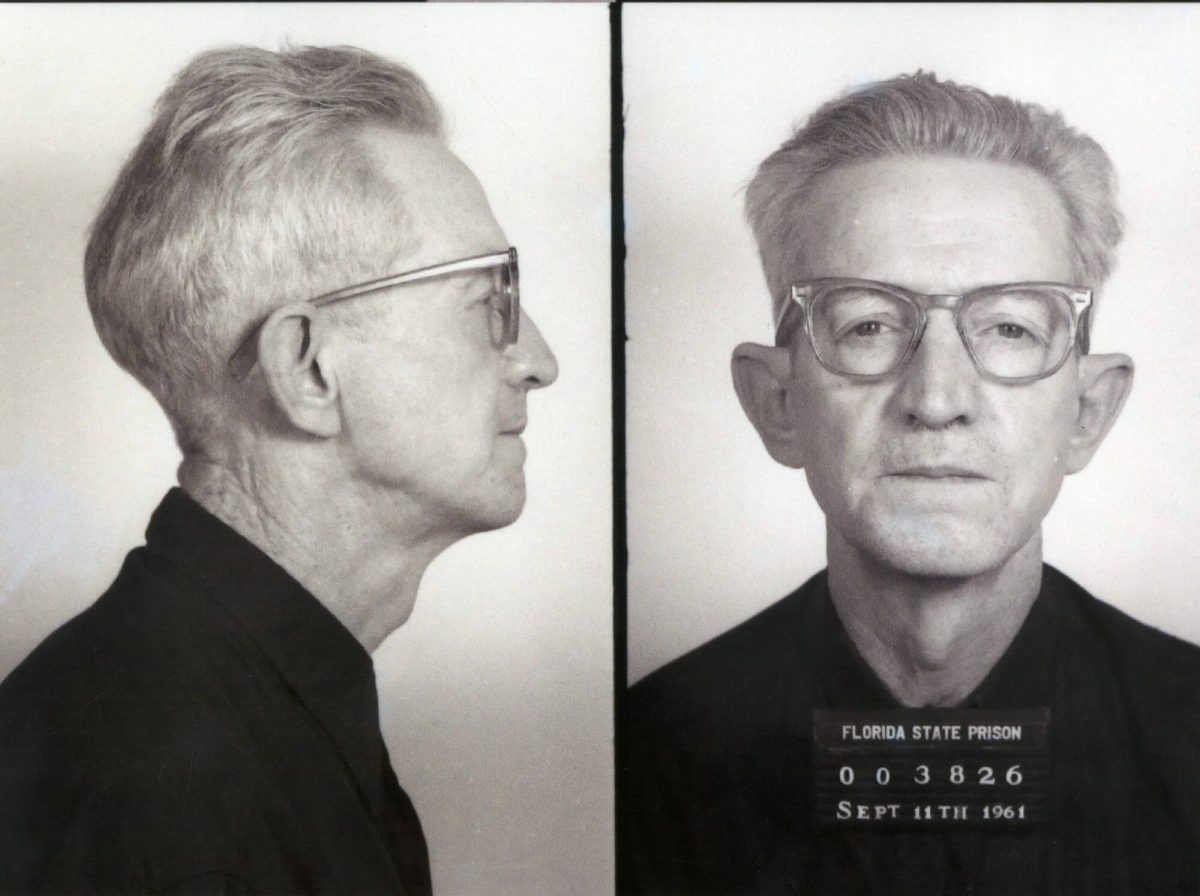

To understand Marbury, you first need to understand the unfiltered political drama of early America. At the time, the nation had two major political parties: the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. Let’s just say they hated each other (think Hamilton-Burr levels of tension but with fewer duels). Federalist President John Adams, having just lost his reelection to his own Vice President-turned-political opponent, Thomas Jefferson, decided to throw a last-minute wrench into Jefferson’s plans. In what history now calls the Midnight Appointments, Adams and his Federalist-controlled Congress created a ton of new judicial positions and stacked them with Federalists before Jefferson could take office. Adams was signing judicial commissions practically until he walked out of the White House. Some were delivered, but others—like the one for William Marbury, who had been appointed Justice of the Peace—were left sitting on a desk when Jefferson took over. Jefferson, being no fan of Adams, ordered his Secretary of State, James Madison, to leave those commissions undelivered.

Enter William Marbury, a man who wanted his job. Marbury, frustrated that his judgeship had been lost in the presidential transition shuffle, sued Madison. He asked the Supreme Court to issue a writ of mandamus–a legal order forcing a government official to do their job—in this case, to deliver Marbury’s commission. Sounds simple enough, but there’s much more to the story. The case wasn’t just about a single piece of paperwork; it raised a much bigger question: Did the Supreme Court even have the power to force Madison to deliver the commission in the first place?

Before reaching a decision, the Supreme Court considered three critical questions: Did Marbury have a right to his commission? If he had a right, and that right was violated, did the law provide a remedy? If a remedy was available, was the Supreme Court the correct body to issue it? Marshall answered the first two questions with a resounding yes—Marbury had been legally appointed, and when a right is violated, the law must provide a remedy. However, the third question led to the case’s groundbreaking conclusion. Now, here’s where things get interesting. The Chief Justice overseeing this case was none other than John Marshall—who, funnily enough, had been Adams’ Secretary of State. That’s right, the same guy who was supposed to deliver Marbury’s commission was now ruling on whether it had to be delivered. Talk about a conflict of interest!

Marshall and his fellow justices faced a puzzling dilemma. If they ruled in favor of Marbury and ordered Madison to deliver the commission, Jefferson’s administration could just ignore the ruling, making the Court look weak. But if they ruled against Marbury, they’d concede that the judiciary had little authority. Instead, Marshall took a third option, and this option changed American law forever. Marshall ruled that while Marbury did have a right to his commission, the Court couldn’t issue a writ of mandamus because the law that gave the Court that power—the Judiciary Act of 1789—was unconstitutional. And just like that, the Supreme Court established judicial review, the power to strike down laws that violate the Constitution. With this ruling, the Court positioned itself as the ultimate interpreter of the Constitution, capable of keeping Congress and the President in check.

To this day, Marbury v. Madison remains one of the most important cases in U.S. history. Every time the Supreme Court strikes a law as unconstitutional, you can thank John Marshall for making it possible. So next time someone tells you the Supreme Court doesn’t have much power, just remind them: they’ve been overruling presidents and Congress since 1803. It all started with a forgotten commission, a political grudge and a Chief Justice who saw potential in the little things.