Imagine a classroom where history and justice collide—that’s the story of Brown v. Board of Education (1954). This case involved a fight that forever changed America’s classrooms, from defining rights to setting the boundaries of government power. Few cases illustrate this power better than Brown v. Board of Education.

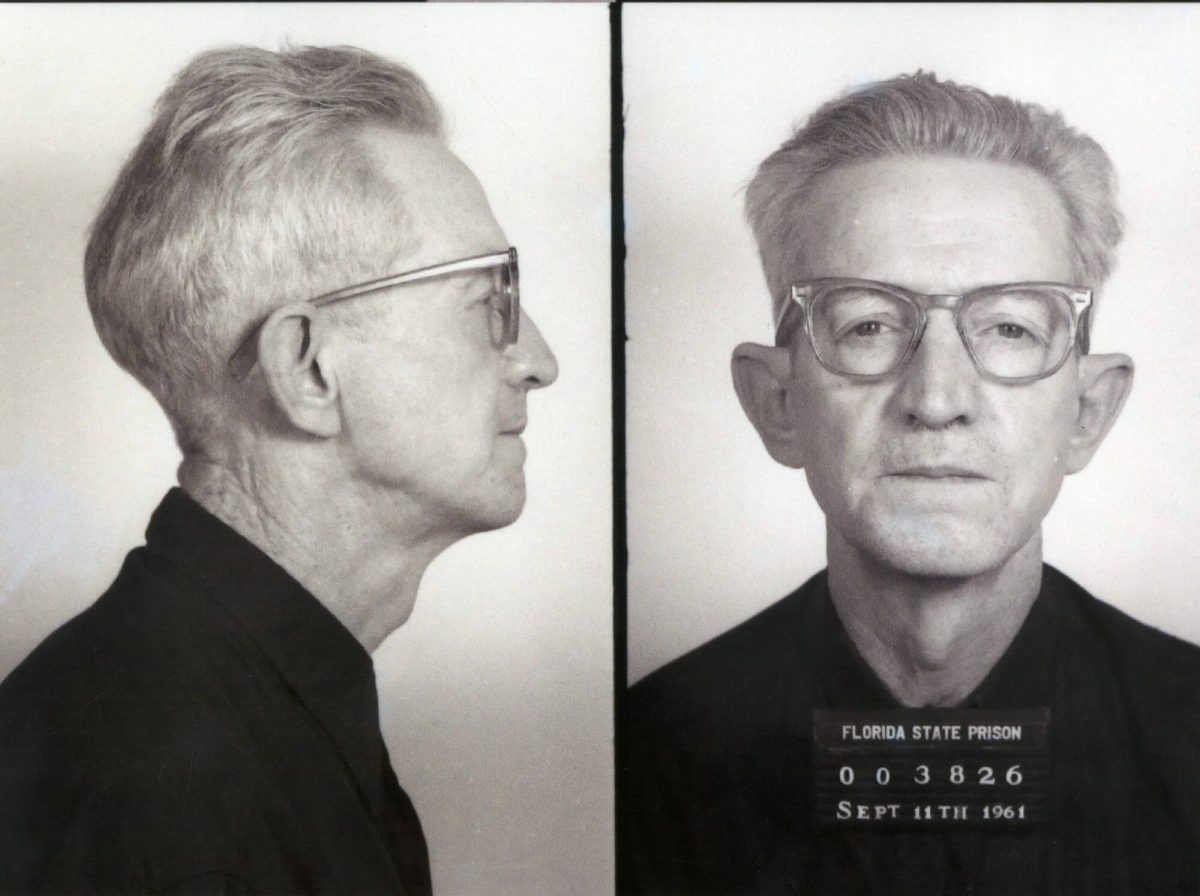

At the heart of the case was Linda Brown, a third-grader from Topeka, Kansas. Her daily walk past a white school to reach her distant Black school made her father, Oliver Brown, join a class-action lawsuit. The goal? To make the Constitution count for his daughter. The case aimed at the 1896 ruling Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld segregation under the “Separate but equal” doctrine. But the Browns, backed by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and Thurgood Marshall, knew that separate schools weren’t just unequal–they were just wrong. Marshall, who later became a Supreme Court Justice, didn’t just argue the law, he also brought science to the stand. The Clark doll tests, where Black children overwhelmingly preferred white dolls, laid bare the psychological harm of segregation. Marshall argued that this internalized inferiority was a lifelong scar inflicted by a segregated society, making it clear that separate could never be equal.

In a unanimous decision, the Court declared that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” striking down Plessy and citing the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. Thus, the court formally ended racial segregation in schools nationwide. But the decision came with a catch. Schools were to integrate with “all deliberate speed,” a vague phrase that let Southern states stall for years.

Surprise! The ruling wasn’t just about justice; it was about optics. Like all civil rights somehow are in this country, it was about politics. With the Cold War raging, U.S. leaders cared more about their international image than justice for Black Americans. Soviet propaganda was eagerly exposing America’s racial hypocrisy. Claiming that following a democratic path, like the U.S., was not the most viable option, often citing America’s treatment of black people, became a reasonable deterrent for prospective countries during the Cold War. Desegregation became a Cold War “PR move” in a way, as a method of silencing critics and winning influence with non-white nations emerging from colonial rule. Thus, the Court chose the ambiguous phrase “with all deliberate speed” when ordering school integration. The justices knew that enforcing rapid integration would spark political chaos and backlash from Southern states (states whose support was critical for national unity during the Cold War). The phrase allowed the U.S. to claim the moral high ground on paper while avoiding immediate enforcement of racial equality. And here’s the hard truth: without the Cold War, Brown v. Board might have turned out completely different. The decision was a landmark not because America cared for Black children but because it needed to “save face” on the global stage. It’s the most crucial part of this case and a stark reminder that civil rights victories often ride shotgun to political interests. But that’s something they won’t teach you in school.

The demise of the Jim Crow Laws truly began with Brown v. Board, which also cleared the path for further civil rights struggles throughout the ensuing decades. It placed Thurgood Marshall on the bench and demonstrated that even the highest court could advance American interests, sometimes via political means and other times through justice, but always with impact.