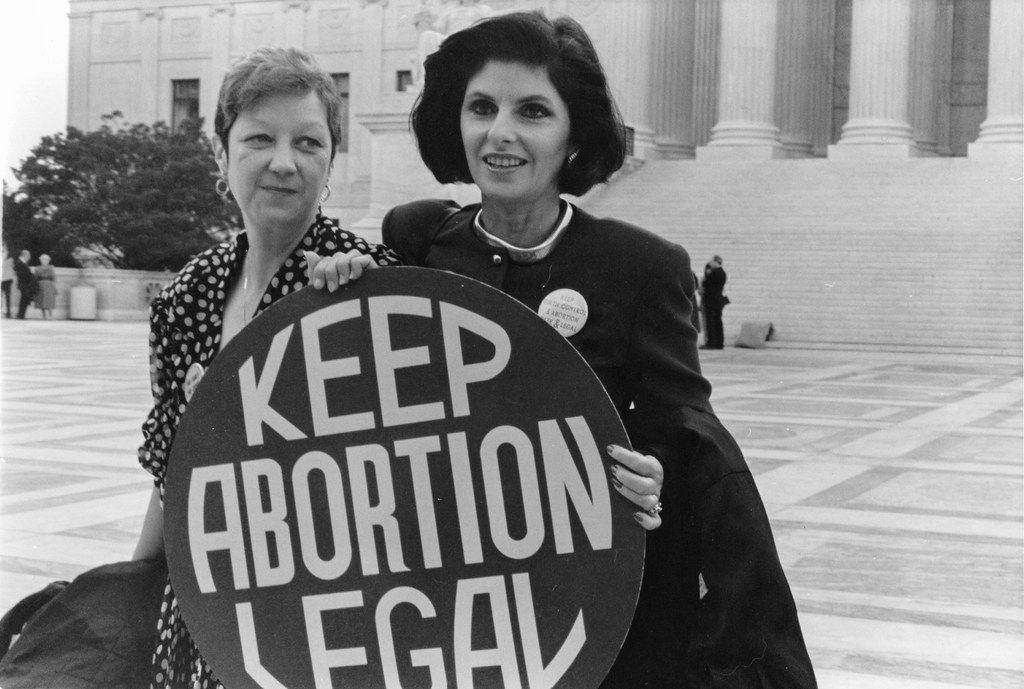

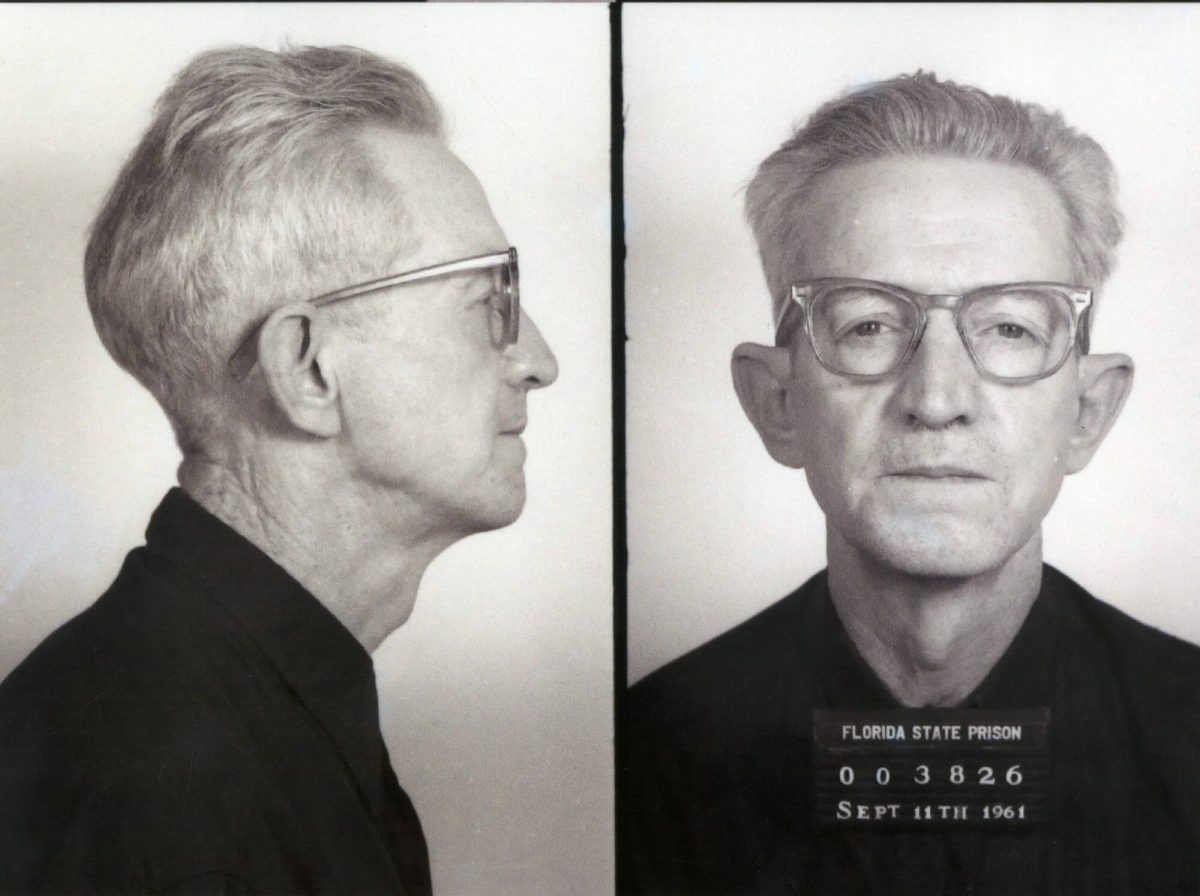

Imagine a society where using birth control pills may land you in legal hot water. Surprisingly, this is Connecticut in the early 1960s, not some apocalyptic nightmare. Dr. C. Lee Buxton and Estelle Griswold established a clinic in Connecticut in 1961 where they gave married couples guidance on how to avoid having children. Among other things, they prescribed birth control, which was so unorthodox at the time that the local government detained them right away. What did they do wrong? They broke a statute from 1879 that said “any drug, medicinal article or instrument for the purpose of preventing conception” may not be used. It was time for Griswold and Buxton to confront the problem head-on–literally. Their strategy was to purposely get arrested to challenge this outdated law to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Griswold and Buxton, who were each fined $100, claimed that the birth control restriction in Connecticut was an infringement on their constitutional rights. From the appellate level to the Connecticut Supreme Court and, in 1965, the U.S. Supreme Court, their battle progressed up the judicial ladder. Attorney Catherine Roraback, who represented Griswold, contended that the prohibition of birth control was not just a terrible policy but also a violation of the right to marital privacy, which she maintained was guaranteed by the Constitution even though the word “privacy” wasn’t explicitly used. In a 7-2 ruling that overturned the statute and formally advanced the idea that the Constitution protects privacy (even if you had to read between the lines), Justice William O. Douglas concurred and wrote the majority opinion–or in the “penumbras,” as Douglas put it.

Where exactly is privacy in the Constitution? In short, it is everywhere and nowhere at the same time. The Court pointed to the First, Third, Fourth, Fifth and Ninth Amendments as creating a privacy “forcefield,” especially within marriage. As Justice Douglas put it, “Would we allow the police to search the sacred precincts of marital bedrooms for telltale signs of the use of contraceptives? The very idea is repulsive.”

And with that, the right to privacy was born.

Griswold didn’t stop at the bedroom door and was about more than just married women and birth control. It became the foundation for decades of landmark cases surrounding privacy issues. Eisenstadt v. Baird, which gave unmarried persons the freedom to use contraception, would not have existed without it. Neither would Obergefell v. Hodges (legalizing same-sex marriage), Roe v. Wade or Lawrence v. Texas (decriminalizing same-sex relationships). The Supreme Court acknowledged for the first time in Griswold v. Connecticut that, although not explicitly stated in the Constitution, privacy is crucial to the liberties that Americans take for granted, particularly when it comes to making decisions regarding their bodies, relationships and homes. It signaled a long-awaited departure from antiquated rulings such as the Comstock laws, which had regulated everything from “obscene” goods to contraception.

In the 21st century, when privacy is increasingly fragile, Griswold reminds us just how vital these protections are. With challenges to privacy-based rulings appearing more frequently, some have even suggested that cases like Griswold be reconsidered. The fight Estelle Griswold, Dr. Buxton and Catherine Roraback took to the courts is far from over.

Griswold v. Connecticut may not always get the same spotlight as Roe or Obergefell, but it’s the reason we fought for those cases in the first place. It’s the case that established, once and for all, that what happens in your bedroom is nobody’s business but yours. And in this era of heightened surveillance, revived morality laws and endless debates over reproductive rights, the question of privacy is more urgent than ever. While dissenters may continue to preach the argument that “the right to privacy isn’t in the Constitution,” just remember, neither is the word “marriage,” “parenthood” or “internet.” But good luck making a legal system without them.