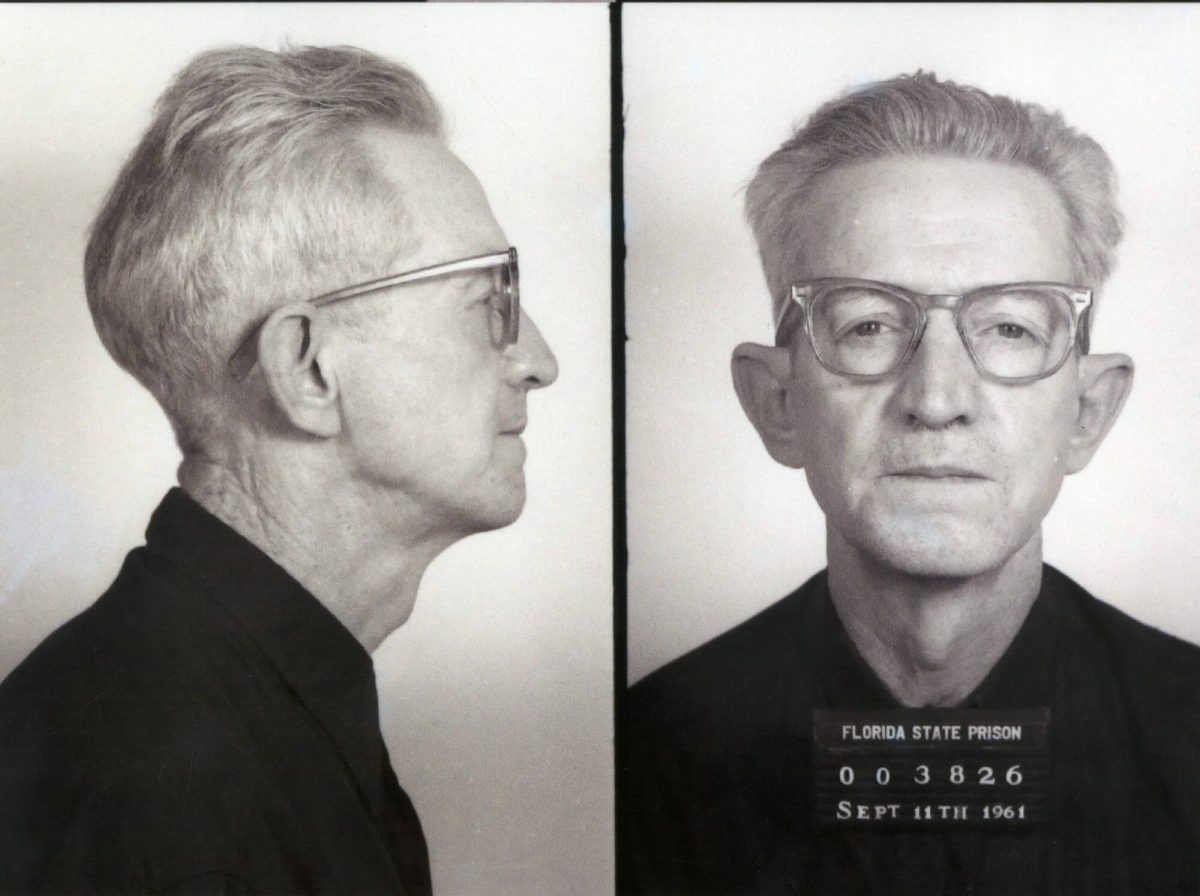

Imagine you’re forced to go to court, accused of a felony and facing the full weight of the state’s prosecution. You have no lawyer, no money and no legal expertise—just your wit, a wrinkled shirt and the vague memory that the Constitution probably says something about your rights. That was Clarence Earl Gideon in 1961. But unlike most people in his shoes, Gideon didn’t just take the conviction and move on. He picked up a pencil and wrote himself into history. Before Gideon v. Wainwright, the guarantee of legal counsel only applied if your life was literally on the line (i.e., capital punishment). Otherwise, tough luck. States could deny you a lawyer and leave you to defend yourself in court. The landmark 1963 decision in Gideon v. Wainwright changed that, and it all started with a handwritten petition from a Florida prison.

Gideon had a lengthy criminal record and had been in and out of jail four times in the past. But he wasn’t violent, just unlucky and perhaps a bit too fond of pocket change and pool halls. When he was arrested for breaking and entering the Bay Harbor Pool Hall, he asked for a court-appointed attorney. The judge denied him, citing that Florida law only allowed counsel in capital cases. So Gideon, armed with nothing but an eighth-grade education and a fierce sense of justice, decided to represent himself. Unfortunately, it did not go well.

Found guilty and sentenced to five years, Gideon did what most would never dare—he used the prison library to write a writ of habeas corpus, petitioning the Florida Supreme Court. They said no. So he went higher. Much higher. He sent his petition to the United States Supreme Court in forma pauperis, meaning that without the money, most people would need to file a complaint. The court took his case, and history began to be made.

With this, Gideon’s case made an ironic switch. He went from having no lawyer to represent him to having the best in the country, Abe Fortas, who later became a Justice himself. The case wasn’t just about Gideon anymore; it was about revisiting Betts v. Brady (1942), a decision that essentially said that indigent defendants did not have the right to counsel in non-capital cases sometimes. That “sometimes” led to a wildly inconsistent justice system, and Fortas knew it. He framed Gideon’s case as a simple one: even a competent, harmless coin-carrying man like Gideon deserves a fair trial. And fair means counsel. Florida, for its part, dug in. Represented by a young attorney fresh out of law school, the state worried that granting counsel to all poor defendants would open the “floodgates” and force the retrial of thousands.

In a rare moment of judicial harmony, the Court ruled unanimously 9-0 in Gideon’s favor. Justice Hugo Black, who had dissented in Betts, finally got his moment. He wrote that the right to counsel is not a luxury but a necessity, so essential to a fair trial that it must be extended to state courts via the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause. The opinion was bolstered by 25 amicus briefs, 22 of which came from states supporting Gideon—yes, states supporting a ruling that would technically limit their own power. When states voluntarily agree to give up a little control for fairness, you know we’re dealing with something fundamental.

Clarence Gideon never became a lawyer or a politician. He was retried (this time with legal counsel) and acquitted. But what he did accomplish was arguably more impactful: he reshaped the criminal justice system for millions who would come after him. He may have started with a bottle of wine and a pocket of coins but ended with a constitutional legacy. So next time someone tells you one person can’t make a difference, tell them about Gideon. He lost his trial—but he won the case.