Halloween crowd surge kills 156 in Seoul, Korea

November 1, 2022

On Saturday night Oct. 29, the Itaewon neighborhood of Seoul, South Korea was packed with tens of thousands of people celebrating Halloween. The joy soon turned to horror, as a major crowd crush took place, killing 156 people and injuring 173 more.

Itaewon, the site of the tragedy, was home to the headquarters of United States Forces Korea. Numerous bars and clubs opened in its alleys to serve American soldiers, and has long been regarded as “Little America” in the heart of Seoul. Since the 2010s, its exotic culture and food scene has made it a popular attraction for both Koreans and foreigners. The relocation of the USFK headquarters in 2018 boosted Itaewon’s popularity. With most of Seoul’s gay bars located in the neighborhood, it is also regarded as the LGBT capital of South Korea. “Itaewon Class,” a hit series released in 2020, helped it gain international fame.

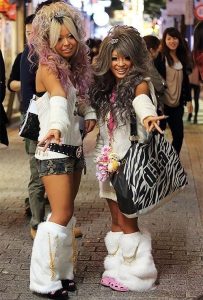

One of the biggest annual celebrations in Itaewon is Halloween, where younger South Koreans became aware of the foreign tradition from learning English as children and it became an opportunity for them to express themselves each year with unique costumes. With its established reputation as a nightlife hotspot and gateway for American culture, Itaewon was chosen as a mecca for those wanting to celebrate Halloween.

This year saw more joy-seekers than usual, due to the uplifting of most social distance measures, including mask mandates outside. In 2019, over 96,000 people used the adjacent Itaewon subway station on the day of the celebration. According to Seoul Metro, the same figure three years later was over 130,000, 30 percent more than prior to the pandemic.

Despite being renowned for its nightlife, Itaewon was never built for mass gatherings. Sitting upon a hilly terrain, the area was developed before the nation started implementing proper urban planning. Itaewon’s main attraction, the World Food Street, is only 5 to 7 meters in width and 325 meters in length. It is estimated that this narrow street and surrounding area were packed with around 100,000 people.

Connecting the World Food Street to Itaewon’s main road is a downhill alleyway behind Hamilton Hotel. The hotel had illegally extended its terrace, further narrowing the 4-meter-wide alley. As the night went on, it was filled with more and more people and around 10:30 p.m., a bottleneck emerged in the middle of the pathway, allowing people little room to breathe or escape. Soon, civilians began falling on and crushing each other.

Paramedics and police officers struggled to rescue the survivors from the chaotic scene and the following morning the massive scale of the disaster became clear, with President Yoon Suk-yeol declared a period of national mourning, which lasted until Nov. 5. Most Halloween-themed events were canceled nationwide. In response to the catastrophe, the Korean Football Association scrapped all street cheering plans for the 2022 Qatar World Cup.

South Korea’s national police was criticized for its response. Despite the predictions of large crowds, only 137 police officers were deployed at the site. While this was more than previous celebrations, their duties were focused on monitoring crime, not crowd control. Most of Seoul’s police force was placed in other neighborhoods to manage political rallies. The earliest calls reporting the stampede were made four hours before the disaster, but there was not much that the local police station could do without external support. Yoon Hee-keun, South Korea’s national police chief, admitted to the failed responsibilities of his organization.

Many of the victims were women in their teens and 20s. Among the 156 people killed, 147 were below the age of 40. Almost twice as many women died as men, with 101 of the deceased being female. Twenty-six of the casualties were foreigners, including two Americans, Steven Blesi, 20, and Anne Gieske, 20.

A senior Marketing major at the University who was studying in the same exchange program as Blesi and Gieske expressed that while she was not close with them, it was horrifying to learn of their fate.

“They say Americans are desensitized because we have mass casualties more than any other country. But I’ve personally never been that close to a tragedy before. I knew the area, street and alleys like the back of my hand…There’s no other way to describe the feeling except simply shocking,” the student said. “I am still wrapping my head around it,” she said. “I live five minutes away from Itaewon so it was my go-to spot for going out or having food. I don’t think I’m ever going to go there again, which really sucks.”

The tragedy is a reminder that stampedes or crowd crushes can happen anywhere at any moment. “I think people should talk about it. They need to be reminded that even seemingly put-together countries are not immune to bad things,” said Serena Classen, a sophomore at the University. “No events or festivities are perfect even if they do their best. It is a learning opportunity for better precautions next time.”

With increasing gentrification, the small shops and restaurants that have made Itaewon popular have been struggling to pay rising rents and many are uncertain of the future of Itaewon. Many shops and restaurants have already been replaced with global brands and franchises. The global pandemic also delivered a severe blow, leaving the neighborhood with countless vacancies.