Excellence and exploitation: ‘King Pleasure’ Basquiat exhibit review

April 29, 2022

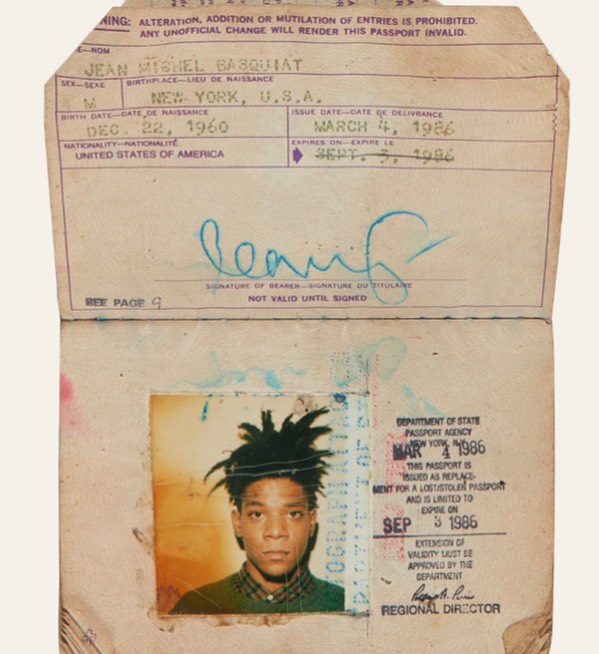

“King Pleasure,” the post-mortem exhibition of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s never before seen art, evokes more questions about who truly knew and loved him. Basquiat’s art has been used for profit in fashion collaborations with brands such as Coach, Urban Outfitters and Converse. Basquiat’s “Untitled” (1982) was sold for $110.5 million. His art was influenced by the abuse he endured as a child and other hardships, including his homelessness.

In photos, Jean-Michel Basquiat looks familiar, I see him in little Black boys proudly bringing their finger painting to their overworked mothers. I see him in Black and Latine teenagers skating through Park Slope full of ambition. I see him in the Black men and women thirty years after his death facing the same ongoing homelessness crisis. His art was made for people of color, marginalized communities and those facing poverty, but in turn, his art is being used for profit, but it was intended for the people.

After Basquiat passed away at the age of twenty-seven, he was praised, adored and exploited. Basquiat was worthy of all the acclaim he received while he was alive. Thirty-five years after his death, it is easier for onlookers to say we have distanced ourselves from the crises faced in the ’80s. However, the white supremacy that upholds police brutality, the homelessness in New York, and the violence against Queer people of color persist. Basquiat would have been appalled to see his art being purchased by billionaires for bragging rights.

However, “King Pleasure” was an intimate look at Basquiat’s life. Even his earlier art from his school days displays defiance toward authority; the haphazard words in Spanish within his work, the clarity of his poetry written with the utmost care and the innocent expressions on his face as a child. At his core, Basquiat was a kid from Brooklyn with a library card and a pen in his pocket. This exhibit showed parts of Basquiat that were deeply human.

Basquiat devoted his life to art, immersed himself in it and graced generations after with his work. But his legacy became a trinket, a Coach purse in someone’s closet, a watered-down version of his values to be palatable for a white audience. Basquiat despised the police, believed everyone deserved affordable housing, was a drug user and loved vehemently.

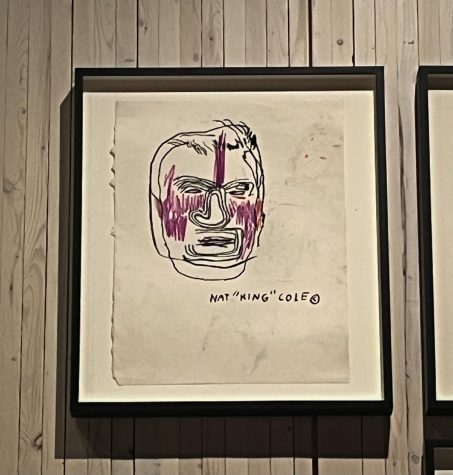

This exhibition is an unadulterated view into his mind curated by his sisters Lisane and Jeanine Basquiat. I do not wish to sanitize his narrative; I respect him too much to do so. Basquiat stripped of his fame is violently human. At an early age, Basquiat admired Nat “King” Cole and Jesse Owens. Basquiat has been immortalized in the same manner; he remains the idol of young artists today.

Displayed in “King Pleasure” on a smudged piece of looseleaf in uppercase letters he wrote, “Stay indoors the street is crazy tonight / Wait for sunlight / We can watch cartoons / I’ll buy you some paint / I’ll buy you some paint and canvas and some professional brushes / If you stay with me until I see my dealer” In death, Basquiat is not alone, we bear witness to all he lived through.

We are still living through the systemic issues reflected in his art, and what a relief that he too, bore witness to our hardship and depicted it onto canvas. Basquiat still speaks for New York even after he has left it.