Incarcerated trans artist makes debut in solo exhibition, ‘Even Flowers Bleed’

September 29, 2022

Tucked away in a ninth-floor art gallery in Chelsea, Jamie Diaz’s debut solo exhibition “Even Flowers Bleed” is a stunning collection of watercolor paintings made between 2013 and 2022 that explore the complexities of queerness and the strength of the human spirit. Anyone entering the exhibition at Daniel Cooney Fine Art without knowing who Diaz is will be shocked to find out that everything was created within a prison cell. However, incarceration is nowhere near the entire story of Jamie Diaz, a Mexican-American transgender woman who creates art to celebrate queer joy.

Diaz was born in Illinois in 1958, grew up in Houston and has been creating art since she was a teenager. Her biography within the exhibition references a broad range of artistic inspiration, ranging from tattoo artist Ed Hardy to the Dutch Masters. While the exhibition itself is entirely watercolors, Diaz has worked in many mediums throughout her life, including tattoo work. Her preferred medium is oil paint, but, due to being incarcerated, she is limited to watercolors.

The exhibition gets its name from her series of still lifes featuring vases of thorned roses and claws dripping blood. In her statement on the exhibition, Diaz explains, “everything bleeds, everything feels pain. We’re not the only ones… even flowers can hurt. That’s just part of nature.”

The pieces all bear common motifs: thorns, claws, little angels and devils. Some feature white doves, a symbol Diaz uses throughout her work to represent the queer spirit. In addition to the still lifes, there are portraits of the artist and her friends as well as more surrealist figures that explore the balance of opposites. Good versus bad, light versus dark; these dichotomies are the theme of pieces like “Raising the dead,” which depicts a violin player who stands on a black ground of thorns against a bright blue sky filled with doves. This contrast shows the balance of joy and struggle that comes from experiencing life as a queer person.

Diaz also shares with viewers her raunchy humor through her comics, focusing on the queer angel and devil characters that are in many of her pieces. In the comics, they serve as protectors and friends, watching over her and reminding her how great she looks. They can get very explicit, and Diaz shared that censorship is something she’s had to deal with when mailing her art out. Diaz’s comics have been in multiple publications and her first full-length comic book, “Queer Angels and Devils,” is being published through A.B.O. Comix, which aims to “amplify the voices of LGBTQ prisoners through art.”

University junior Pat Steinger shared that the comics were their favorite part of the exhibition. “I love how real they were and the contrast between the colorful cartoon style and somewhat serious topics they discussed created a really interesting dynamic that tells you a lot about the artist,” they said. “I also really enjoyed that you get to see Jamie’s self-image evolve over time through her art.”

The self-portraits of Diaz display the unique and powerful talent that she is. The piece “Queer Spirit” shows her strutting confidently down the street in pink leggings and a signature tight black shirt, carrying a pride flag below a rainbow and a dove with the words “Our flaming queer hearts will not be denied” on the piece. On a letter with information regarding her parole date, Diaz drew another self-portrait labeled “The Naked Truth” where she strides naked outside below the same rainbow and dove, pulling open her chest cavity, declaring, “it’s time to get out of here and start doing some good for the LGBTQ community.”

Diaz has been incarcerated in a men’s prison in Texas, serving a life sentence for aggravated robbery since 1996. In 2025, she will be eligible for parole after serving nearly 30 years of her sentence.

Along with the art, the exhibition had a binder containing “Coming Out of Concrete Closets: A Report on Black & Pink’s National LGBTQ Prisoner Survey,” the most extensive collection of information from LGBTQ+ prisoners ever collected. Diaz shares her own stories as an incarcerated transwoman through pieces like “Me and My Jellyroll,” a comic where she discusses how she received a disciplinary report for styling her hair and argues for the right to self-expression regardless of where someone is. On the first page, she explains why she does her work, writing, “to educate and to support each other and create a positive influence for our trans and queer communities. To try and make things better for people like us.”

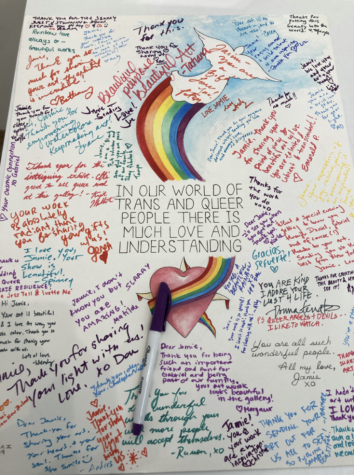

On a table in the gallery, there is a piece Diaz made titled “In Honor of Being Queer,” which bears the same rainbow and dove appearing in so many of the paintings along with a heart and bleeding thorns. In the middle of the page, Diaz writes, “In a world of trans and queer people there is much love and understanding.” Visitors are invited to add their names and a note to the once empty space on the paper, which now is full of notes of gratitude and encouragement to the artist displaying the love and understanding of the queer community that Diaz celebrates in every piece.