Modern Hollywood is exploiting race and femininity

October 18, 2022

It seems as if the film industry has progressed so much since outwardly problematic films such as “Birth of a Nation” or as apologist as “Gone with the Wind.” In the modern age, Hollywood displays itself as something inclusive, something woke, something aware. Yet, modern Hollywood presents itself through a theater of progressiveness. The industry has assigned values to cultural progression and its relevance to then profit off those values. This concept joined with a systemic and historical precedent of the exploitation of those employed, has created a sinister environment to produce “progressive stories.”

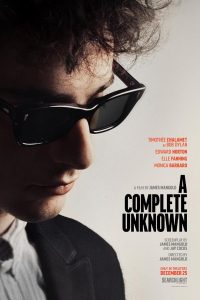

The timeliest discourse surrounding a new age of exploitation has been provoked by Andrew Dominik’s “Blonde.” “Blonde,” released via Netflix on Sept. 28 tells a fictional biography of the iconic Marilyn Monroe. Defenders of the film use this vehicle of image and iconography to justify the volatile nature of the film. “Blonde” depicts several scenes of heinous acts inflicted upon Monroe to accomplish a story of how abuse permeates all stages of life. It seeks to use Monroe as a martyr, a golden age tragedy of the objectification and commodification of women’s bodies in Hollywood. This sentiment sounds alright—and whether this is accomplished is completely up to the viewer, but where the theater of progressiveness truly reveals itself is an ongoing battle between whether or not an industry rooted in the male gaze serializes and chronicles that story for entertainment.

“It seems that every few months, a feminist tale of women is presented through the media. But rarely do these outlets ever truly understand what it is to be a woman,” said Eliza Miller, University Film & Screen Studies major. “If it is a tale of a woman suffering, it is sexualized down to the very core. Why? Because the people that run Hollywood are men.’

Miller continued saying, “Years ago a man choosing to tell the story of a woman was seen as a beautiful thing, but what qualifications does a man have that a woman doesn’t? Especially when it comes down to the conditions that women go through. It seems so mind-boggling to me that in the 21st century, men are still telling women’s stories.”

The nature of any art stems from the abstraction of reality. Whether that abstraction is minimal in a hyperreal presentation or maximal in an expressionist landscape, art is subjected to the lens of a missed reality. This aspect of artistry becomes problematic, however, when it concerns the abstraction of real people. Especially in a film like “Blonde,” they use a real person’s genuine struggle and reduce it into an image. Whatever grounds in which Joyce Carol Oats sought to explore in her original novel had been bastardized in this adaptation by Dominik.

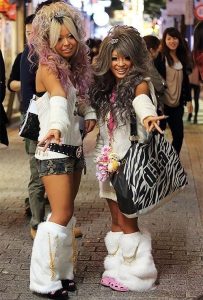

In a similar view, Hollywood’s roots in the objectification of femininity can also be seen in the exploitation of race and culture. It’s people using identity and race as a vehicle to tell stories that concretely do not belong to them. It’s been acknowledged that the “white savior,” a common trope that presents a fantasy that non-white issues can somehow only be resolved by a white person. This is perhaps the easiest and most apparent instance of Hollywood’s exploitation of race; it satisfies the profitable perception of inclusivity while preserving a perception that Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) are subject to white executives.

However, more recently we see a trend in the consumption of colored cinema to be an area in which to displace any subconscious racist guilt—in that the consumption of this media substitutes any real industrial change. Every few years the main media unifies behind one film that oversees a topic of race and marginalization and persuades the public that it is sufficient or that it is the peak of progress. Through an Asian cinematic lens, we see films like “Crazy Rich Asians,” or even “Parasite” and “Everything, Everywhere, All At Once,” which became the poster child for progress in Hollywood. The exploitation and reduction of these few films become a monolith for a race whose consumption of such becomes a decry of ignorance. The fact that films like these are getting widespread attention is wonderful, but the “Black Panther-ification” of these films—as in the consumption of these films become acts of wokeness—is not only absurd but embarrassing for its participants.

The pervasive issue with all these controversies stems from the people who seek to tell these stories and their proximity to the subject matter at hand. I attribute the widespread critical distaste towards Dominik’s warped view of the subject at hand. As someone whose fundamental experience is so detached from the subject matter, no amount of research or virtue by Dominik could perfectly encapsulate the unique feminine experience.

This sentiment spreads beyond the feminine experience but to race, as well. The woke values are filled with tokenized and arbitrary inclusion. Hollywood’s output would see white as the status quo for casting and for color to be a novelty. This is not to say that there is no room for stories by non-marginalized groups or that they are of any lesser value. But rather it should be: those of non-marginalized groups being able to tell their own stories and their voices becoming the louder ones, rather than having a third party speaking on behalf of them.